A research team has devised and tested a scheme based on advanced optical-physics principles, which uses active submarine optical-fiber data cables also to sense ocean-floor earthquakes and ocean-surface swells.

The previous part of this article established the context for “piggybacking” seismic-sensing capabilities onto an existing undersea fiber-optic cable. This part looks in more detail at the project’s basis and results. Note that the physical cable is not a single, uniform assembly but instead changes jacketing and protection depending on location along the path (Figure 1). There are also optical amplifiers every 100 kilometers to boost the optical power by up to 20 dBm.

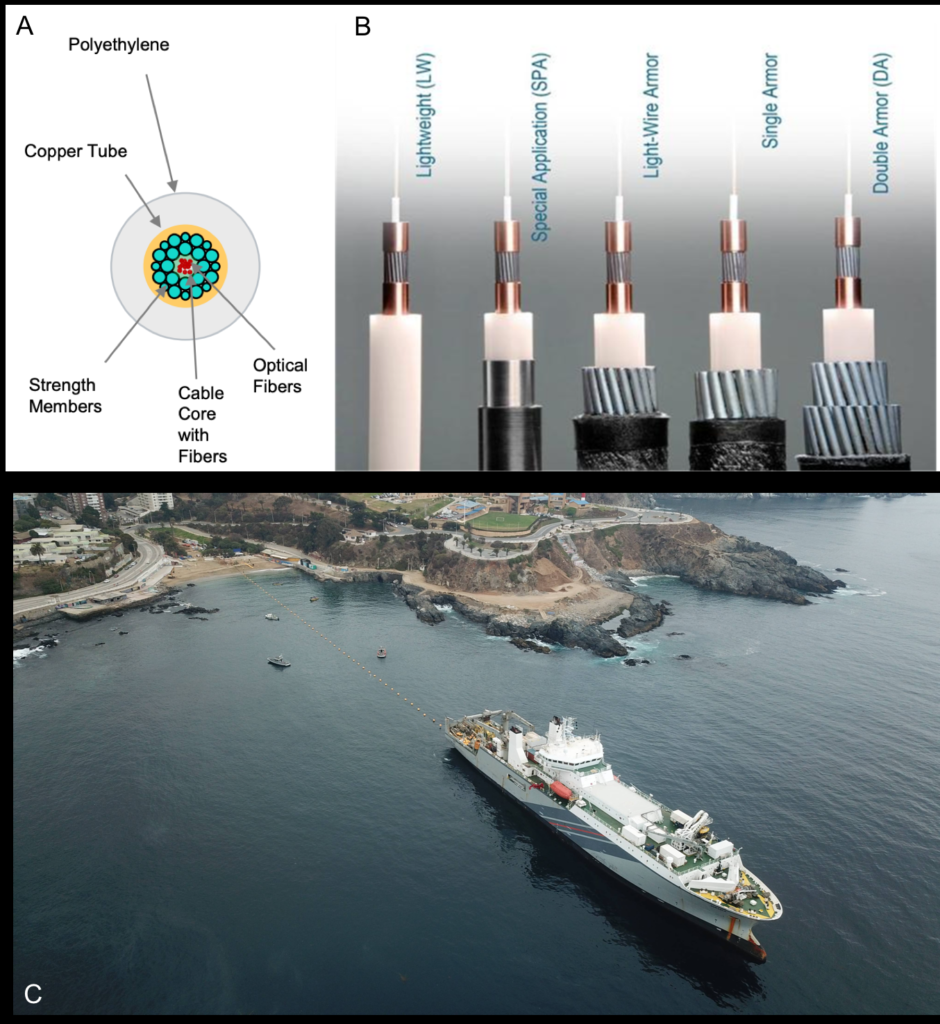

To maximize throughput and achieve the highest possible data rates, one factor which cable-system operators monitor is the polarization of the light (usually designated as a state of polarization or SOP) that travels within the fibers. By controlling the electric field’s direction associated with this polarization, multiple signals can be multiplexed through the same fiber simultaneously (Figure 2). At the receiving end, optical instrumentation checks the SOP of each signal to see how it is dynamically changing along its journey – a type of distortion which results in the optical signals getting cross-couple. They then interfere with each other, degrading the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and increasing bit error rate (BER). The Stokes parameter is a widely used factor which characterizes this optical-signal polarization.

For fiber in a “quiet” environment and not affected by time-varying external perturbations, the Stokes vector of the output polarization is constant. However, when the fiber is instead exposed to time-dependent disturbances such as stretching, twisting, pressure, or bending, that changes couples to the fiber’s birefringence. The birefringence of each section of the optical cable then changes, and the Stokes vector of the output polarization changes and varies as well.

The polarization can change within the cable due to temperature fluctuations, lightning strikes, and minute mechanical motion. Still, the first two effects occur mostly in land-based, not submarine cables. In contrast, the ocean temperature remains nearly constant. There are fewer environmental disturbances, so the deep-water Curie cable is not as “noisy” due to those first two factors as its terrestrial counterparts. The researchers found that polarization along the Curie Cable remains quite stable over time. That stability is key, allowing the researchers to detect the third factor – mechanically induced strain – in the cable.

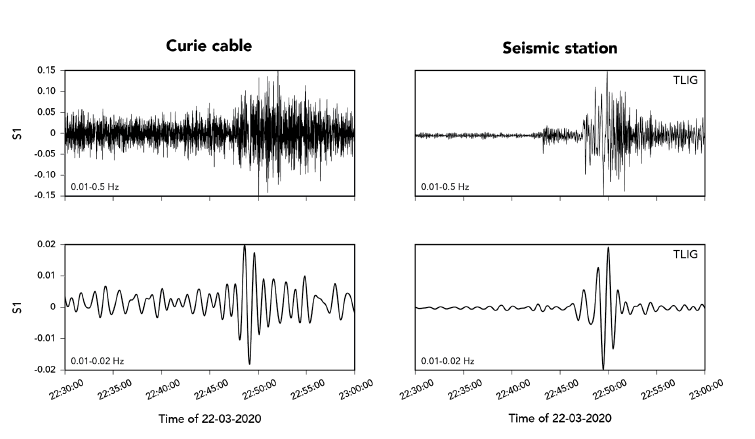

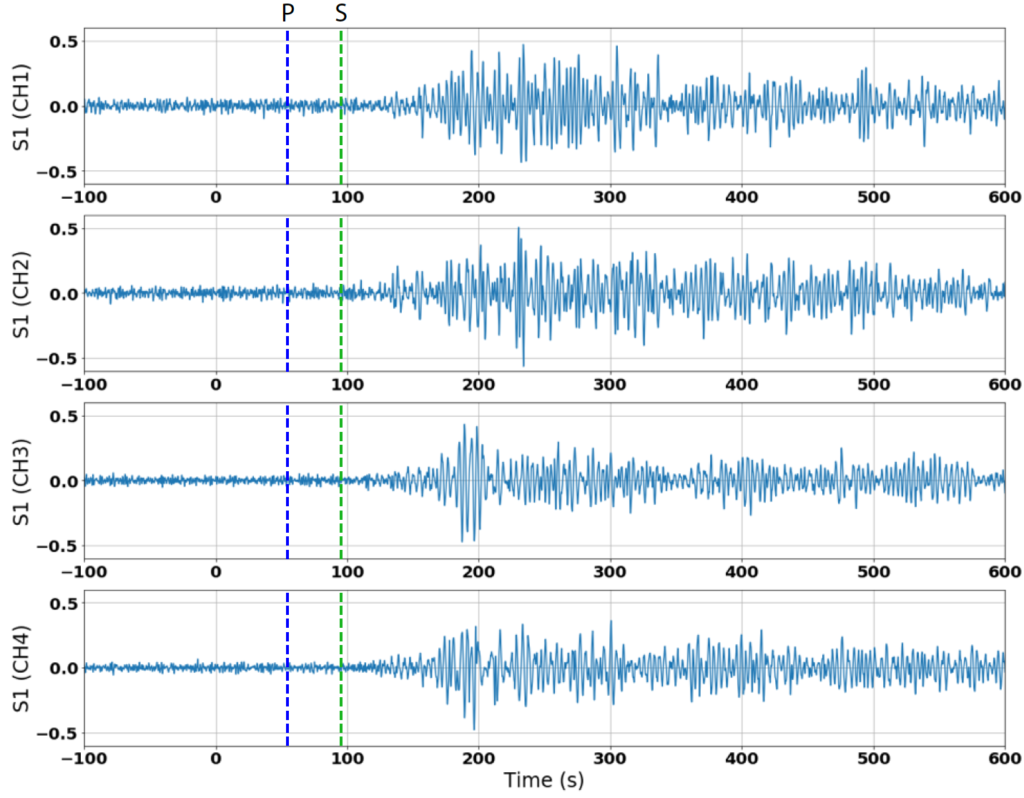

However, during earthquakes and when storms produce large ocean waves, the polarization changes suddenly and dramatically. These changes can be detected with the existing monitoring equipment and suitable data-analysis algorithms. As a result, the entire length of a submarine cable acts as a single sensor in a hard-to-monitor location. Polarization is measured frequently, often as much as 20 times per second, so when an earthquake strikes close to a particular area, it could be detected in seconds (Figure 3).

Note that this is a very low-bandwidth phenomenon, with variations occurring slowly in the range of tens of millihertz (1 MHz = 0.001 Hz) to a few hertz. That’s a very different spectrum compared to what most electronic and optical engineers are used to thinking about and measuring (but not unusual for mechanical engineers and real-world processes – think of temperature), so low-frequency stability and the low drift inherent in the sophisticated polarization test instrumentation is necessary.

The team recorded approximately 30 ocean storm-swell events and 20 moderate-to-large earthquakes across the nine-month continuous observation period, including the August 4, 2020, 5.8 magnitude submarine earthquake offshore from Guatemala (Figure 4).

“This new technique can really convert the majority of submarine cables into geophysical sensors that are thousands of kilometers long to detect earthquakes and possibly tsunamis in the future,” said Prof. Zhan. “We believe this is the first solution for monitoring seismicity on the ocean floor that could feasibly be implemented around the world. It could complement the existing network of ground-based seismometers and tsunami-monitoring buoys to make the detection of submarine earthquakes and tsunamis much faster in many cases.”

He also noted that because this method does not require specialized equipment, laser sources, or dedicated fibers, it is highly scalable for converting global submarine cables into continuous real-time earthquake and tsunami observatories. The project’s full details are in their paper “Optical polarization–based seismic and water wave sensing on transoceanic cables” published in Science; there is also posted Supplementary Material with detailed optical-physics equations and analysis, graphs of results, and much more.

Related EE World Content

Optical amplifiers, Part 1: Applications and considerations

Optical amplifiers, Part 2: Basic implementations

The first undersea transatlantic cable: An audacious project that (eventually) succeeded, Part 1

The first undersea transatlantic cable: An audacious project that (eventually) succeeded, Part 2

Advancing Undersea Optical Communications

Researchers Develop Novel Framework for Tracking Developments in Optical Sensors

Dual-photodetector optical sensor module in 0.88mm package enables thinner wearable designs

Optical Fibers Can ‘Feel’ Materials Around Them

What types of problems can fiber optic kinetic sensor solve?

External references

- Zhan et all, Science, “Optical polarization–based seismic and water wave sensing on transoceanic cables”

- Zhan et all, Science, “Supplementary Material”

- Purdue Dept. of Physics, “Waves & Oscillations: Polarization of Light”

- Northwestern University, “Measurement of the Stokes parameters of light”

- Science Direct, “Stokes Parameter”

- Nikon Microscopy, “Principles of Birefringence”

- Olympus Life Science, “Optical Birefringence”